Detailed Description

Detailed information

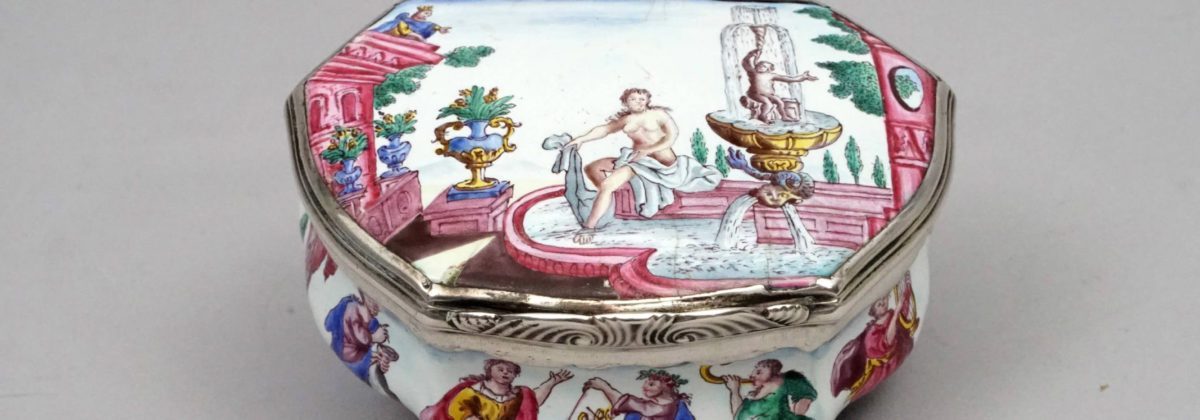

The box has an ovular form with six sides, mounted with silver hinges around the rim, which open on one side. The base of the box undercuts to create a natural curvature, on which the box gracefully perches. The exterior has been decorated with enamel on which motives from the old testament adorn each side of the box.

The silver hinge lies above the curved base of the box and outlines the painted enamel scene on the exterior surface of the lid. This silver rim is highlighted by the slight ridge outlining the form and shape of the box. Whilst the front of the rim is decorated with undulating forms. These forms centre at the point which is used to open the lid of the box. Hereby the ornamentation acts as a decorative element whilst also easing the accessibility of use. The multi-use/interpretation is a significant element in the compositional narrative of the box.

A centrally significant scene, placed upon the exterior of the lid, is that of Bathsheba bathing. (2Sam 11:2) “David arose from his bed. And walked upon the roof of the King’s house, and from the roof, he saw a woman washing herself, and the woman was very beautiful to look upon.” David’s act of adultery and Bathsheba’s bathing are compelling narratives throughout art history and iconography. The argument for Bathsheba being naked and thereby being at fault for seducing the king is a central concept when interpreting the narrative. The present box displays Bathsheba without clothes but with a cover, washing her feet, unlike medieval illuminated books like that of Jean Bourdichon. An initial glance at the box sees the scene as a beautiful and decorative display of femininity in a magnificent courtyard setting. David, clothed in blue and yellow, peering from the balcony in the top left corner of the composition creates an additional significance to the composition. Hereby bringing into question the female’s role in society and furthermore her interpretation in the history of art.

Notably, the second scene lies on the interior surface of the lid. Displayed here is the story of Susanna Bathing. As told in the Old Testament, the beautiful Susanna went into her garden one hot day to take a bath. Two men secretly observed her there. They waited for the moment when Susanna would send away her maids so as to seduce her. However, Susanna resisted their approach virtuously, thus entering the annals of history and art as a heroine of Chaisty and piety. Susanna would be arrested for supposedly seducing the men with her lack of clothes, however, both men mistakenly recall the tree under which they met Susanna differently, thereby justifying her innocence. The present box shows the scene in the height of the action, Susanna barely clothed stretches her arm at the two men, pushing them away, under a green tree. The nude is often used in art as a representation of the beauty of the female form, whilst also as a symbol of the lust of man. Alternatively, to the previous narrative depicted on the snuff box, this scene shows the female as a heroine, whereby although naked, she attains a level of influence over the men. The dynamism of the scene, seen in the exaggerated movement in the clothes of the men, juxtaposed with the stretched arm of Susanna creates an enlivened narrative within the box, in comparison to the previous scene.

Finally, Judith and Holofernes, an icon of female rage, are depicted on the underside surface of the box. The narrative suggests that the Assyrian King Nebuchadnezzar sends General Holofernes to besiege the Jewish city of Bethulia. Judith, aims to seduce Holofernes and then slay him, herself. In succeeding, she would win a decisive battle for the Israelites. The character of Judith combines the piresty, “womanly” virtues, much like the previous narratives, alongside strength. This becomes a central theme for artists exploring power dynamics and gender identity. Especially in the possibility of depicting Judith as a Femme Forte or even a Femme Fetale. The addition of this scene on the underside of the box, alongside the previous two, creates an evolving dynamism in the historical narrative of the portrayal of women in art.

The outer surfaces of the snuff-box, along the sides, depict five women playing typical instruments notable in the old testament. The shorter, a horn of either ram or goat, a tambourine, clippers, bells, and a lyre, similar to a harp but smaller and with fewer strings. This depiction of a musical scene creates an atmosphere of passive yet decorative significance. Disguising the enamel paintings as merely ornamentation, displaying the passive role of women as a figure of beauty with which we are historically accustomed to. The rear, of the enamel sides, depicts two guards guiding a male clothed in blue and yellow away from the scene. The central male in each of the main scenes is also clad in blue and yellow, suggesting a connection.

Compositionally the snuff box is uniform in its use of colour, thereby suggesting its furthered connection throughout the three narratives alongside also being aesthetically pleasant. Whilst the pink motives and floral ornamentation suggest the box’s use for a woman, also emphasising the potential significance.

Luxury Enamel Goods

Toilet sets and/or boxes produced with white enamel are referred to as “email de Saxe”. Their chief feature is the colourful paintings on thewhite enamel surface. This technique was mostly used in Dresden by Dinglinger, in Berlin by the workshop of Fromery and in Augsburg.

In the early eighteenth century, French snuff boxes (tabatières) made of gold and enamel or of other precious materials, were increasingly fashionable in Germany. These were mostly used for the storage of snuff tobacco, but also for powder, pills and bonbons.

The ascent to power of Frederick the Great (1712-86) resulted in a restriction on the importation of such “boxes” from France. The goal was to encourage the local production of such wares. Frederick was a great collector and user of such snuff boxes, just as Heinrich von Brühl (1700-63), the head of the Meissen Porcelain Manufactory.

The Production of such boxes with luxurious floral motives became a popular and common practice throughout upper-class Europe. The inclusion of detailed religious motives, in the present box, gives it a certain degree of significance and intrigue, beyond simply decorative florals. Great examples of comparable works using similar techniques during the same period can be found in the collection of the MAK – Austrian Museum for applied art: https://sammlung.mak.at/sammlung_online?&q=email%20dose .

Literature:

Frey, Angelica, ‘How Judith Beheading Holofernes Became Art History’s Favoruite Icon of Female Rage.’ April 4. 2019. URL: https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-judith-beheading-holofernes-art-historys-favorite-icon-female-rage (14.11.2022)

Honour, Hugh und Fleming, John, Lexikon Antiquitäten und Kunsthandwerk, Beck-Prestel: München, 1984.

Koeppe, W., Le Corbeiller, Cl., Rieder, W., et al. (Hrsg.), The Robert Lehman Collection, XV : Decorative Arts, The Metropolitan Museum New York/Princeton University Presse: New York, 2012.

Rupp, Herbert, Steiskal-Paur, Richard, Art Cult Center – Tabakmuseum (Hrsg.), Snuff Boxes oder Von der Sehnsucht nach lüsternen Nase, Katalog zur Sonderausstellung des Österreichischen Tabakmuseums vom 30. November 1990 bis 31. Jänner 1991, Wien: Austria Tabakwerke Aktiengesellschaft, 1990.

Schäfer-Bossert, Stefanie, ‘The Representation of Women in Religious Art and Imagery, Discontinuities in “Female Virtues.” Sp. 137-156 von Gender in Transition.

Steingräber, Erich, ‚Email’ In: Reallexikon zur Deutschen Kunstgeschichte, Bd. V (1959), Sp. 1–65; in: RDK Labor, URL: http://www.rdklabor.de/w/?oldid=93187 (14.11.2022)